Will Increased Lifespans Cause Overpopulation?

Any discussion of rejuvenation biotechnology almost certainly includes the subject of overpopulation and the objection that medical advances that directly address the various processes of aging will lead to an overpopulated world. Such dire predictions are a common theme in many discussions involving advances in medicine that could increase human lifespans.

Overpopulation is a word that gives the simple fact of population growth a negative connotation. It implies that an increase in the number of people will harm our lives in different ways, such as famine, scarcity of resources, excessive population density, increased risks of infectious diseases, and harm to the environment.

This concern, first raised by the work of 18th century reverend and scholar Thomas Malthus, has been a constant theme in both popular fiction and early foresights related to population growth. However, is it actually well-founded? We will be taking a deeper look at the historical and present population data and showing why overpopulation is unlikely to happen.

To get you started, the X10 team has made a two-part short video series about the overpopulation concern.

What is the population, and how will it grow in the future?

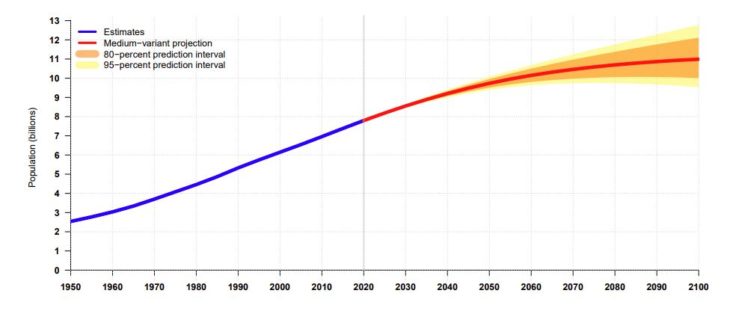

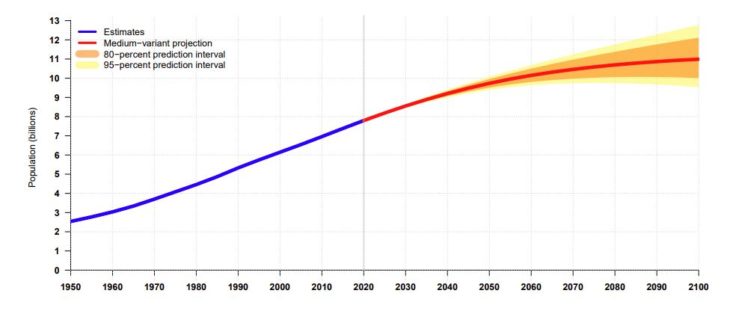

Since the 1960s, both birth rate and population growth have been gradually falling. This will probably lead to a complete halt at 11 billion people near the year 2100. Here is a chart from the United Nations Population Prospects 2019 edition showing the corresponding projections [1].

Fig 1. Population of the world: estimates, 1950-2100. World Population prospects 2019.

Here we can see the continuous, red trend line gradually levelling out into a straight horizontal line. While the population continues to grow, it is at a slower pace than at any time since 1950. However, before talking about why population growth is predicted to stop, let’s investigate why the population is even growing.

In order to ensure population growth, the number of children born per year must surpass the number of deaths in a given country. Typically, a fertility rate index equal to 2.1 is enough for the population to renew without growing in numbers, but a higher birth rate will lead to stable population growth.

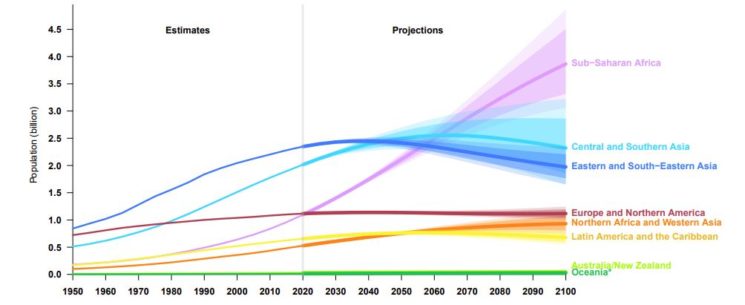

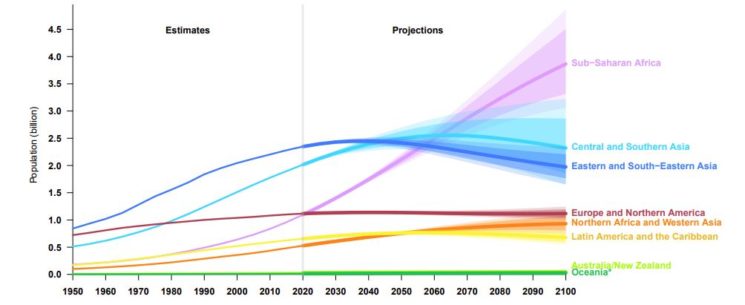

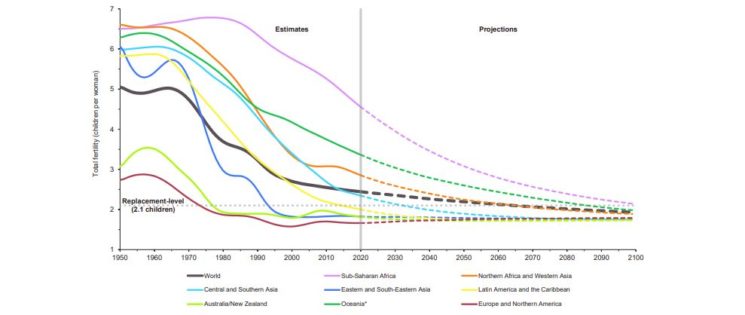

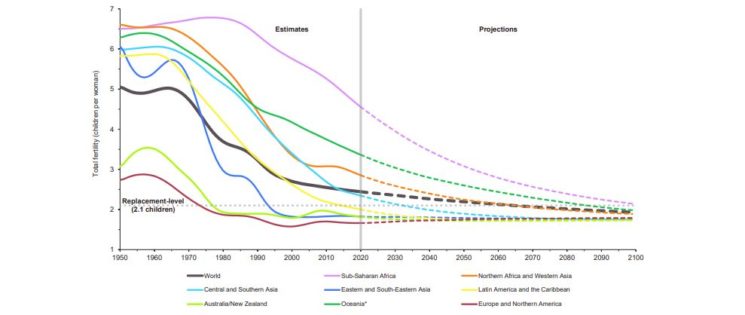

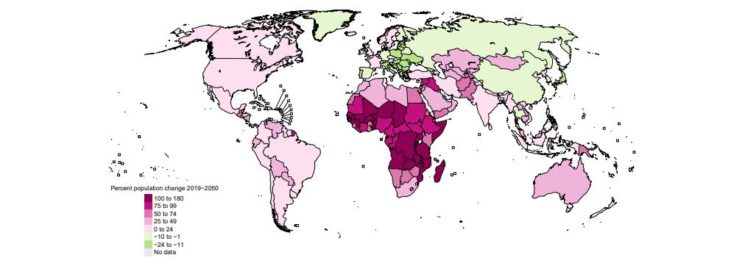

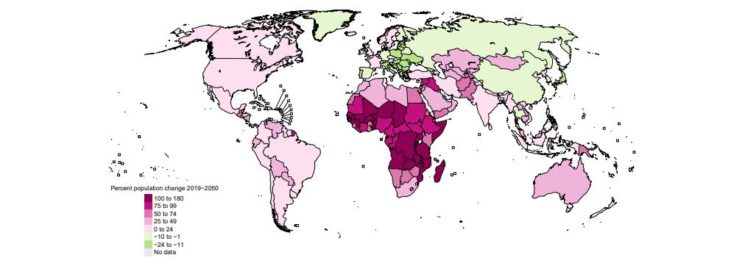

In the illustrations below, you can see the global map of fertility and the projection of population growth by major regions [2]

Fig 2. World Population 1950-2100. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision, Data Booklet.

Fig 3. Total fertility 1950-2100. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision, Data Booklet.

The biggest contributors to the current level of population growth globally are India and several African regions, while many countries (especially in Europe) face depopulation because of their low birth rate. Sub-Saharan Africa will account for most of the growth of the world’s population over the coming decades, while several other regions will begin to experience decreasing population numbers.

Our intuition may tell us that it is unlikely that the least developed countries would be producing most of the population; after all, the standards of living in developed countries make for better conditions to have more children. However, in reality, there are many factors that can lead to a decline in birth rate during the transition to a developed country: education (access to education for women typically postpones marriage and childbirth), unemployment (families try to control their family size to use fewer resources), and access to contraceptive techniques and cultural norms of using them, to name just a few [3].

Economic development is known to affect the time of birth; for example, recession encourages childbirth later in life [4]. National policies to combine work and family life also represent an important factor that may affect fertility rate in both directions. Globalization will “deepen” (in a world-systems theory sense) the less technologically advanced countries, making it very likely that the “higher birth rate” issue in these countries will also decline.

There is supporting evidence showing that moving to an advanced, industrialized economy changes the birth rate of immigrants. The fertility rates of immigrants to the US have been found to decrease sharply in the second generation [5]. Other studies demonstrate that the presence of immigrants does not compensate for declining birth rates [6].

Fig 4. Declining birth rate leads to gradual slow down of the population growth. World Population Prospects 2019: Data Booklet [7].

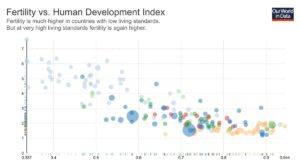

The relationship between the level of the development of a country and fertility can be seen in the next chart. It is worth noting that when the Human Development Index (HDI) becomes higher than 0.85, country development starts promoting the birth rate again [8]. However, this kind of situation is very rare, historically, and therefore not significant enough to shape global population projections.

Fig 5. Fertility vs HDI Index. Data source: United Nations Human Development Index (HDI), UN – Population Division (Fertility), 2015 Revision, Gapminder. Source

Thus, the least developed countries are more likely to have higher birth rates because people there have no reason to postpone childbirth, nor are measures for contraception widely accessible. The only factor holding back population growth in these regions may be the high level of child mortality and overall mortality due to infectious diseases and undernourishment.

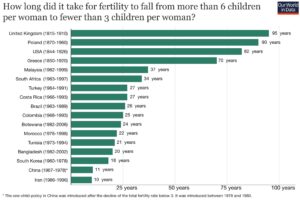

With sustainable development goals focused on the solution of both problems, Africa has the potential to become the biggest human factory in our history. However, taking into account how fast fertility rates can fall because of the adoption of new technologies, this is far from certain.

Fig 6. How long did it take for fertility to fall from more than 6 children per woman to fewer than 3 children per woman? Data source: The data on the total fertility rate is taken from the Gapminder fertility dataset (version 6) and the World Bank World Development Indicators. Source: OurWorldInData.org.

But won’t we run out of space?

In all projected future scenarios for Africa, its population will continue to grow. Today, there are 7.4 billion people on Earth. We are used to thinking that this is already too much, but is that true? First of all, let’s see how much space on Earth we humans actually take up. In 2012, the team of the project “Per Square Mile” led by Tim de Chant produced an infographic showing how big a city would have to be to house the world’s 7 billion people.

The city limits change drastically depending on which real city is used as the model and what its population density is, but this still gives us an idea of how much of our beautiful planet is really inhabited and how much spare space we still have.

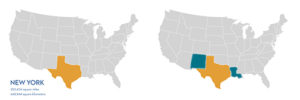

If the projection of population growth by the United Nations is correct, in the next 84 years, there will be about 11 billion people. This means that if all of humanity were concentrated in a land area with a population density similar to New York, it would at most occupy the size of 3 US states by 2100.

2012 2100

Fig 7. 7 bln city with population density of New York/11 bln city with the same population density. From the “Per Square Mile” project by Tim de Chant. Note: the picture at right is modified by the article authors to illustrate the potential growth. The state of Texas is about 700,000 square kilometers, which corresponds to about 7 billion people. The states of Texas, New Mexico (about 315,000 km^2), and Louisiana (about 135,000 km^2) combined represent 1,150,000 square kilometers, which corresponds to about 11.5 billion people by 2100.

Does this mean that population growth is not an issue? From the point of view of the space we humans need, likely so. However, our species’ survival is dependent on many other factors, such as the environment necessary to produce our food and other goods.

Are we going to run out of food?

We should admit that it is about fifty years too late to be concerned about extensive population growth and its consequences, such as famine, because the highest birth rate and population growth was observed from the 1960s to the 1980s. Our population grew by one billion people in just 14 years (going from 3 to 4 billion); however, no big societal or economic challenges were encountered.

Moreover, the next two billion increases in population appeared in 13 and 12 years, respectively [9], but once again, no famine caused by the deficiency of global food production followed [10]. The famines of the second half of the 20th century were provoked by how the food was distributed. Factors such as administrative incompetence of local governments, wars and natural disasters happening several years in a row played the greatest role in creating famine during this period.

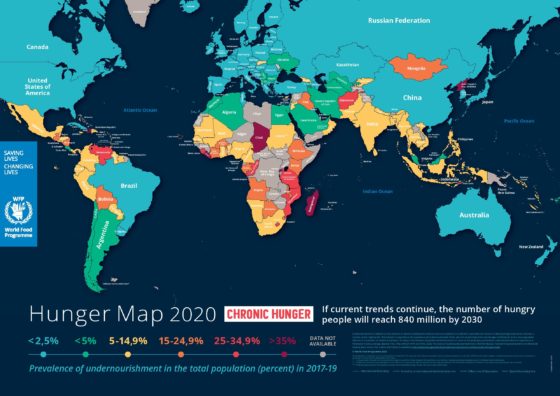

Today, global society is taking measures to eradicate hunger worldwide by 2030. This is very likely to be the case, as the number of people suffering from hunger is decreasing fast. In 2012, it was one in eight, while in 2015, it was already one in nine, which corresponds to 795 million people. Below, you can see the Hunger Map by the World Food Program illustrating the progress.

Fig 8. World Hunger map 2020 by the WFP

If we compare the food supply in 1965 and in 2007, we can clearly see that overeating is more of a global issue than undernourishment, as in most countries, the calorie intake has grown significantly. This could not have happened if our society was suffering from food underproduction, as the food would not be available to overeat, and problems such as obesity would not be so prevalent.

Fig 9. Food supply 1965 vs 2007. Source: Gapminder statistics.

Astoundingly, this means that a population explosion has passed relatively unnoticed – all thanks to the “Green Revolution” (rapid development of new agriculture techniques, such as fertilizers, irrigation and selection). The concern that there will be a food shortage in the future neglects further technological advances such as aquaponics, hydroponics, aeroponics, vertical farming, 3D-printed housing, algae farms, and many other technologies that could provide enough food for all.

The need for more food production represents an excellent opportunity for entrepreneurs, so it is unlikely that the development process of new technologies would suddenly stop, especially taking into account the objective need for rapid changes due to environmental issues.

According to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Livestock’s long shadow”, in 2006, livestock represented the biggest of all anthropogenic (i.e., due to human activity and with potentially harmful side effects) land uses, taking up to 70% of all agricultural land and 30% of the ice-free terrestrial surface of the planet [11].

Scientists admit that while it is still possible to expand agricultural land in some countries in accordance with the increasing need for food, this expansion cannot go beyond the limits of the carrying capacity of our planet. The report states that livestock is responsible for about 18% of the global warming effect, 9% of total carbon dioxide emissions, 37% of methane and 65% of nitrous oxide. Water use for livestock represents about 8% of all human water use (7% of this being used for feed irrigation).

New technologies can provide solutions for the numerous environmental issues related to traditional farming. For instance, hydroponics offers around 11 times higher yields while requiring 10 times less water than conventional agriculture [12]. The energy needs of a hydroponic facility are much higher (up to 80 times more), but thanks to emerging clean renewable energy technologies, this increased demand may not be an issue [13].

Today, there are many companies engaged in the creation of lab-grown meat, such as Supermeat and Memphis Meats. Making a laboratory into a farm is beneficial in many ways, starting from less pollution and fewer greenhouse gas emissions (mostly caused by animal digestion processes).

Sterile conditions in the lab lead to decreased risk of infections and allow the exclusion of antibiotics from the process of meat production. Lab-grown meat can be designed to contain less fat or even fats and proteins with new characteristics (for instance, essential Omega fatty acids).

With less space necessary for laboratory meat production and no waste, it will be possible to ensure disseminated local production in order to cut transportation time and reduce the usage of preservatives. The same system can be used to grow fish meat as well, thus reducing the impact of fishing and fish-farming on the environment. It is interesting to note that not only meat but also other animal-derived products, such as leather, can be produced in a lab, like is done by Modern Meadow.

There are attempts to create new edible products that taste like meat but are completely without animal ingredients, such as Impossible Foods. The recently created vegan ‘Bloody Burger’ by Impossible Foods “uses 95% less land, 74% less water and emits 87% fewer greenhouse gas emissions than its cattle-derived counterpart”. By concentrating on the heme molecule, the mixture apparently “looks like meat, tastes like meat and sizzles like meat“.

These solutions are also great from an ethical point of view, as this technology can reduce animal suffering. The rate of transition to these new ways of animal product creation is widely dependent on political will and social support. It is important to note that there is also significant progress regarding access to drinking water. During the Millennium Development Goals period (1990-2015), it is estimated that, globally, use of improved drinking water sources rose from 76 per cent to 91 per cent. 2.6 billion people have gained access to an improved drinking water source since 1990.

The MDG target of 88 per cent was surpassed in 2010, and in 2015, 6.6 billion people used an improved drinking water source. There are now only three countries (all located in sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania) with less than 50 per cent coverage, compared with 23 in 1990 [14]. New technologies for cheap water desalination and water collection from the air are also helping to improve the situation.

If population growth is not exactly an issue, then what is?

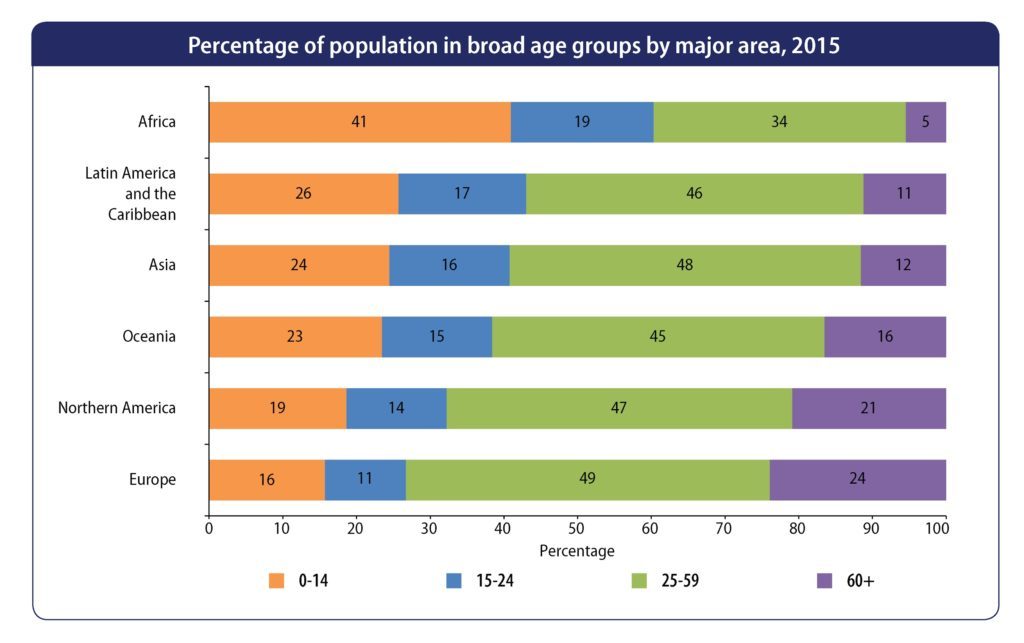

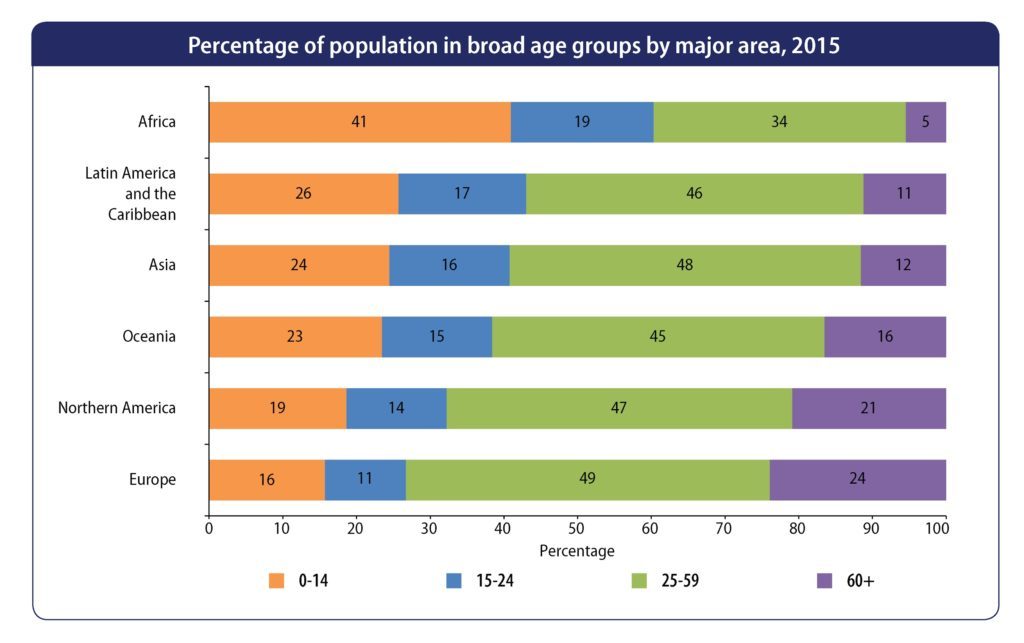

What we really should be concerned about is the age structure of the population. Regardless of the level of technological development, its core are the people of working age who are producing goods, paying taxes, and supporting the non-working groups, such as children and the elderly – the latter needing the most resources because of the state of their health.

Due to population aging, the share of working-age people is shrinking while the share of people who are at least 60 years old is growing. Population structure change is the most evident in Europe and Northern America, while the “Global South” has not experienced it yet – but will experience it in the next few decades.

Fig 10. Percentage of population in broad age groups by major area in 2015. Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015). World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Data Booklet. ST/ESA/SER.A/377

Soon, one third of the population worldwide is going to be aged sixty or over, which means more social protection and healthcare expenditures and more working age people involved in nursing the elderly. However, it would be wrong and unjust to see the elderly as a burden, while these people have contributed so much to the incredible progress that our society has made.

They have all the same human rights as everyone, including the right to life and right to health. As age-related health deterioration is the main reason why society has to provide so much support to the elderly, it would be only logical to see the development of rejuvenation biotechnologies as the way to improve the situation.

What would life be like if we introduced rejuvenation technologies globally?

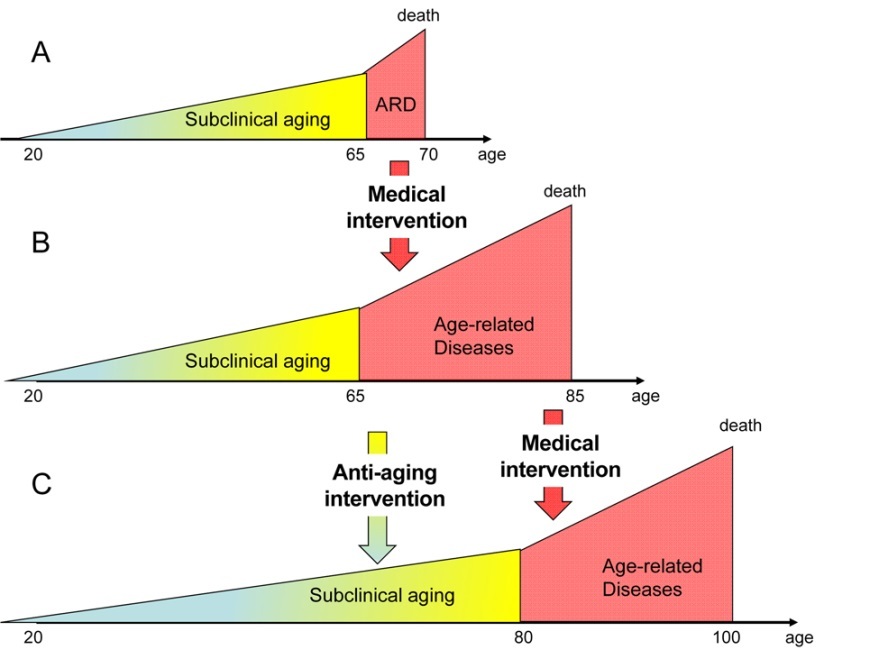

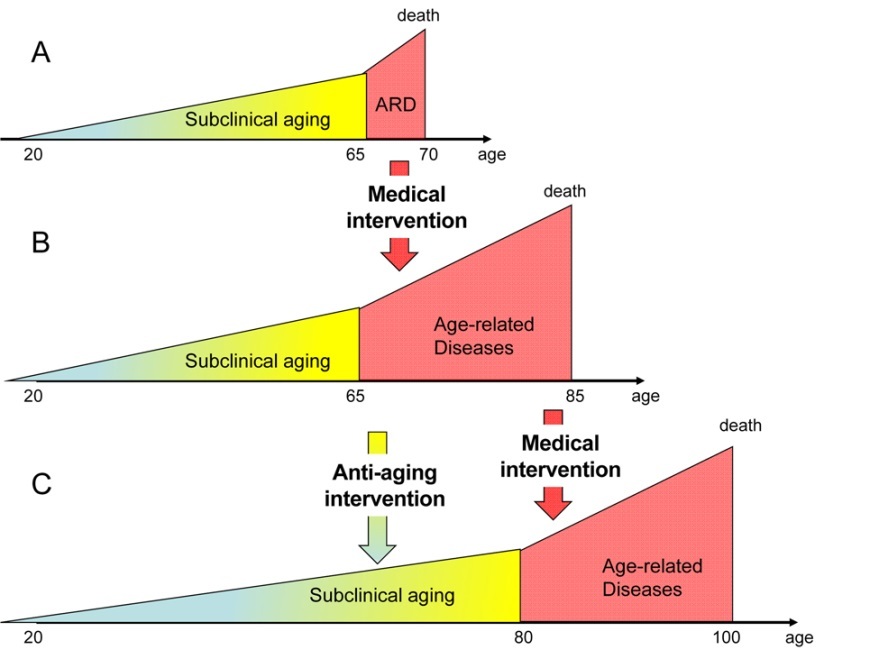

Before the era of universal medicine, people who managed to reach their sixties were still in relatively good health. However, once the onset of age-related diseases began, they died very quickly.

Modern medicine has changed that by slowing down the development of age-related diseases, hence extending the period of productivity. The downside is that this has also extended the period of illness, because treatments to prevent age-related diseases are not yet introduced into universal clinical practice.

In the near future, new interventions to slow down the aging process will become accessible, and then a shift will occur: the period of youth and adulthood will be extended due to better health, and the period of illness will be significantly postponed. In their sixties, people will remain as strong and vital as 40-year-old people are today. Some leading scientists predict that this may also lead to maximum lifespan increases of up to 150 years or more.

This is, of course, hard to prove, because as with many other things in human history, it is a unique situation that has never happened before, but some studies have proposed how aging would look given these three scenarios [15].

Fig 11. A:Pre Universal Medicine, B: Current medicine, C: Slowing aging. Source: Blagosklonny, M. V. (2012). How to save Medicare: the anti-aging remedy. Aging (Albany NY), 4(8), 547-52.

Whilst it is too early to be overly optimistic, we still should mention that apart from these three scenarios, there is a fourth possibility called negligible senescence. Negligible senescence in nature happens when a species does not display signs of aging, regardless of the passage of time. A number of species exhibit negligible senescence, including the rougheye rockfish (Sebastes aleutianus).

The ocean quahog (Arctica islandica) and some kinds of turtles are also negligibly senescent, but they still die because the expansion of their shell ultimately limits their movement. More examples can be found here at the excellent HAGR (Human Ageing Genomic Resources) database.

At some point in time, medical technologies may become so sophisticated that they will be able to bring all of the processes of aging under medical control. If that is the case, then aging will always remain at a subclinical stage, because the repairs to our bodies will keep up the pace with damage accumulation, allowing people to look and feel young for an indefinite period of time.

Most likely, it will take decades for medical science to progress this far, but we should also admit that some of the technologies necessary for this transition already exist, e.g., stem cell therapies, early nanorobots, CRISPR and gene therapies, immunotherapies, senolytics, and geroprotectors (drugs that slow down the aging process).

How will increased lifespan affect population growth?

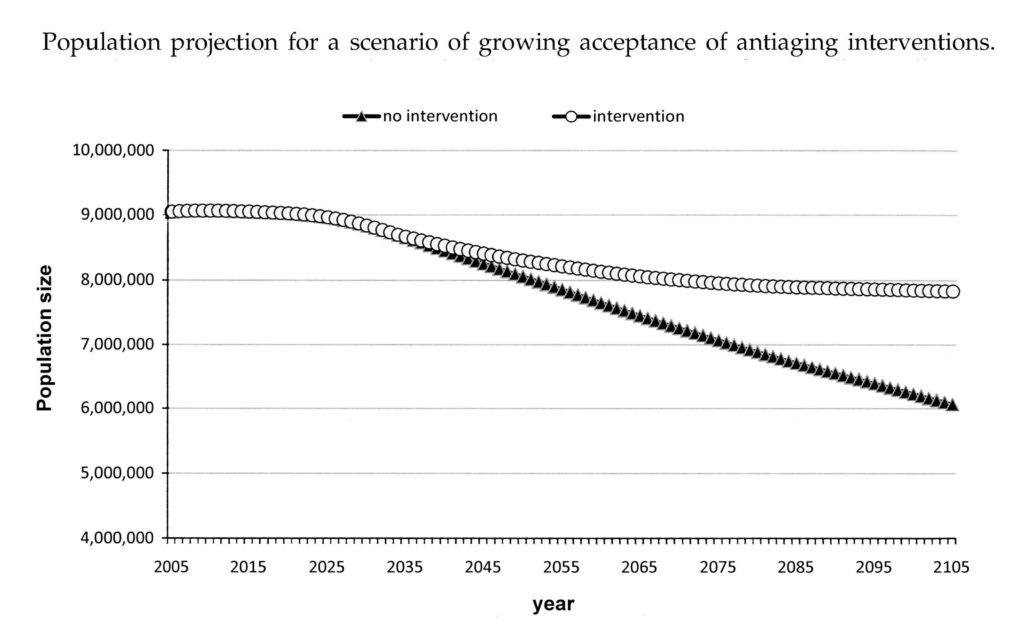

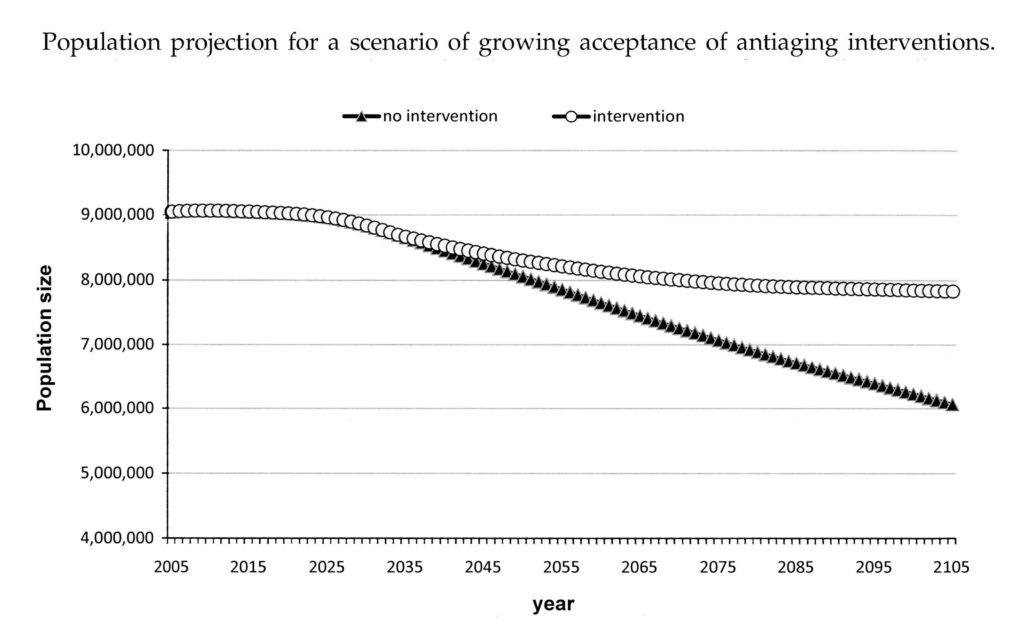

The possibility of significant life extension using medical interventions was not even considered by the academic community until recent years, so there were not many projections of how increased lifespans and negligible senescence would affect population growth. However, a few years ago, such a projection was done for Sweden.

One of the more realistic scenarios is one where only a small share of the population accepts negligible senescence technologies at the beginning (this could be due to a slow dissemination process, ethical or religious objections that people have to overcome, or a high cost of the new technology) with a gradual increase (1% added to the negligibly senescent group each year). It is assumed that some small share of the population will never accept these technologies and will age in the traditional way.

In this case, population change in Sweden will not lead to population growth but can, to some extent, mitigate the process of depopulation over 100 years of medical innovations [16].

Fig 12. Population projection for a scenario of growing acceptance of antiaging interventions. Projection of the Swedish population until year 2105, assuming the negligible senescence scenario for initially small proportion of population (10%), with growing acceptance rate over time. Life extension interventions start at age 60 years, with 30-year time delay from now.

This might be the likely scenario in most developed countries. Taking into account that new technologies tend to be expensive even for developed countries’ middle classes, the developing countries most possibly will reach the same level of implementation later in time, when their fertility rate will be already affected by the index of development. In this case, the fall of their population growth will be smaller due to decreased population mortality.

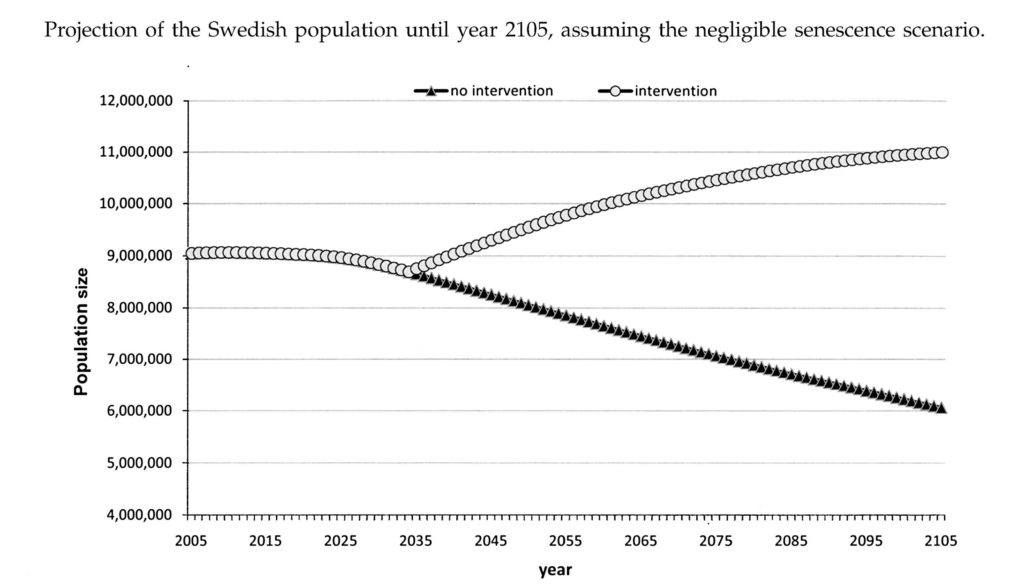

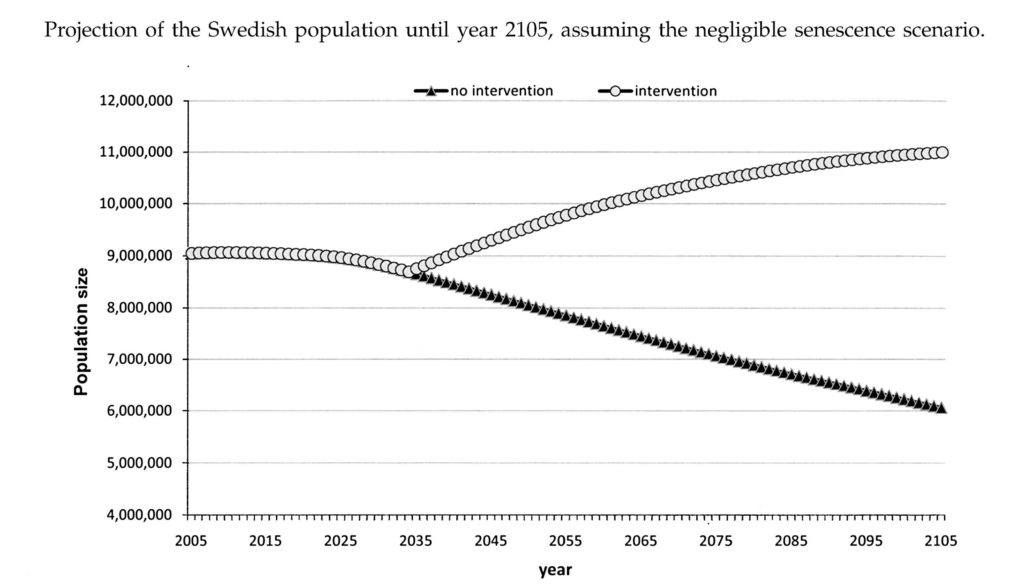

In a more optimistic scenario, where all the population has access to negligible senescence technologies and they are applied to everyone who is at least 60 years old, population growth in 70 years will be around 22%. The earlier the application, the bigger the population growth. If negligible senescence technologies are applied at the age of 40, then the estimated population growth will be nearly 47% in 70 years.

Fig 13. Projection of the Swedish population until the year 2105, assuming the negligible senescence scenario. Life extension interventions start at age 60 years, with a 30-year time delay from now.

There are three main conclusions we can make based on this data.

- The growing share of people using negligible senescence technologies could help optimize the balance between workforce and retirees, hence maintaining economic development. People who are at least 65 years old will be about one-third of the global population in 2100, so we are talking about 3-4 billion old people who could be healthy and productive or ill and frail, depending on which strategy that global society implements.

- Negligible senescence is a synonym of good health, which means that the burden of age-related diseases and their social consequences will be mostly eliminated.

- Population growth, surprisingly, will not be as dramatic as is often imagined, leaving a significant period of time for adaptation, adequate measures of population growth control, and new territories’ development.

Is mitigating aging not only a need but also a legal obligation?

Even if negligible senescence remains a long-term goal, the emerging technologies to address the various aging processes [17] represent a unique opportunity to maintain older people in good health, allowing them to enjoy healthier lives, remain active, learn new skills, and contribute to the development of society. We owe them our present well-being. Not only have these people contributed a lot to create the things we have now, including better nutrition, healthcare, and a comfortable and safe habitat, they have also worked hard to change traditions and wisdom and helped to carry the concept of equal human rights forwards. This is why it is especially poignant to understand that geroprotective technologies and their potential are being underestimated and that they are not receiving the level of social approval and support that they rightly deserve.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution, the objective of the WHO is “the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health”. It is worth noting that WHO defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [18]. While this definition may seem quite spacious, it was made this way purposefully to ensure that member states’ activities in improving the health of their people would never stop.

Conclusion

The need for constant improvement of health is now a universal consensus.

Aging represents the root cause of severe diseases, such as cancer, Alzheimer’s, stroke, Parkinson’s, heart disease, COPD, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis and atherosclerosis, leading to disability of the elderly and to a wide range of negative social consequences, which makes it the perfect target for the global healthcare system [19].

These diseases can only be cured if the actual aging processes are directly addressed and halted while the damage is repaired or reversed by medical interventions. Therefore, according to WHO and United Nations policy, this means that global society has an obligation to eventually cancel aging in order to achieve the highest possible level of health for all people.

Author: Elena Milova, Steve Hill

Source: Lifespan.io is a nonprofit advocacy organization and news outlet covering aging and rejuvenation research.

Literature

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015). World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Volume II: Demographic Profiles (ST/ESA/SER.A/380).

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015). World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Data Booklet. ST/ESA/SER.A/377.

- Mather, M. (2012). Fact sheet: The decline in US fertility. Population Reference Bureau, World Population Data Sheet.

- Lanzieri, G. (2013). Towards a ‘baby recession’ in Europe?. Europe (in million), 16(16.655), 16-539.

- Nargund, G. (2009). Declining birth rate in Developed Countries: A radical policy re-think is required. FV & V in ObGyn, 1, 191-3.

- Camarota, S., & Ziegler, K. (2015). The Declining Fertility of Immigrants and Natives. Center for Immigration Studies.

- UNITED NATIONS DEPARTMENT FOR ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS. (2019). World Population Prospects 2019: Data Booklet. UN.

- Myrskylä, M., Kohler, H. P., & Billari, F. C. (2009). Advances in development reverse fertility declines. Nature, 460(7256), 741-743.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (1999). The World At Six Billion. ESA/P/WP.154.

- Gráda, C. Ó. (2007). Making famine history. Journal of Economic Literature, 45(1), 5-38.

- FAO, U., & Steinfeld, H. (2006). Livestock’s long shadow: Environmental issues and options. Rome:[sn].

- Barbosa, G. L., Gadelha, F. D. A., Kublik, N., Proctor, A., Reichhelm, L., Weissinger, E., … & Halden, R. U. (2015). Comparison of land, water, and energy requirements of lettuce grown using hydroponic vs. conventional agricultural methods. International journal of environmental research and public health, 12(6), 6879-6891.

- REN21. 2020. Renewables 2020 Global Status Report (Paris: REN21 Secretariat).

- Unicef. (2015). Progress on Sanitation and Drinking-Water: 2015 Update and MDG Assessment. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland.

- Blagosklonny, M. V. (2012). How to save Medicare: the anti-aging remedy. Aging (Albany NY), 4(8), 547-52.

- Gavrilov, L. A., & Gavrilova, N. S. (2010). Demographic consequences of defeating aging. Rejuvenation research, 13(2-3), 329-334.

- López-Otín, Carlos et al.(2013). Hallmarks of Aging. Cell , Volume 153 , Issue 6 , 1194 – 1217

- World Health Organization. (2014). Basic documents. World Health Organization.

- Kennedy, B. K., Berger, S. L., Brunet, A., Campisi, J., Cuervo, A. M., Epel, E. S., … & Rando, T. A. (2014). Aging: a common driver of chronic diseases and a target for novel interventions. Cell, 159(4), 709.

Source Lifespan.io

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.