Exposing fibroblasts to the Yamanaka factors for exactly 13 days has yielded substantial results.

Researchers from the Reik lab at the Babraham Institute have used the four Yamanaka reprogramming factors (OSKM) in order to epigenetically rejuvenate cells by 30 years, according to one epigenetic clock.

Reprogramming just beyond the threshold

Previous experiments have shown that while exposing cells to the Yamanaka factors rejuvenates them, it induces pluripotency to turn them into stem cells, thus causing them to lose their cellular identities (and thus function). Attempting to expose cells to these factors just long enough to achieve rejuvenation while allowing them to retain their identities has been a long-standing problem.

The researchers of this study used an approach that exposed cells to enough reprogramming factors to push them beyond the limit at which they were considered somatic rather than stem cells – but only just beyond. The fibroblasts that were reprogrammed in this way retained enough of their epigenetic cellular memories to return to being fibroblasts once again. The researchers refer to this novel method as maturation phase transient reprogramming (MPTR).

A very strong upside with a few downsides

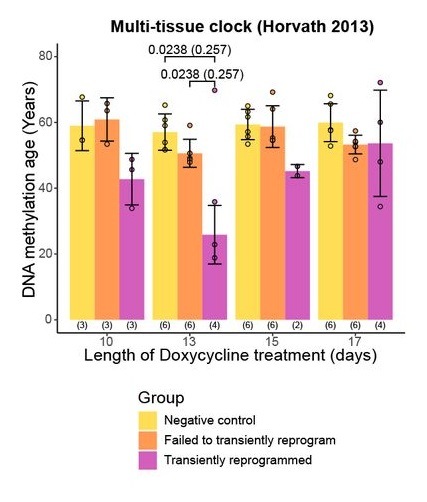

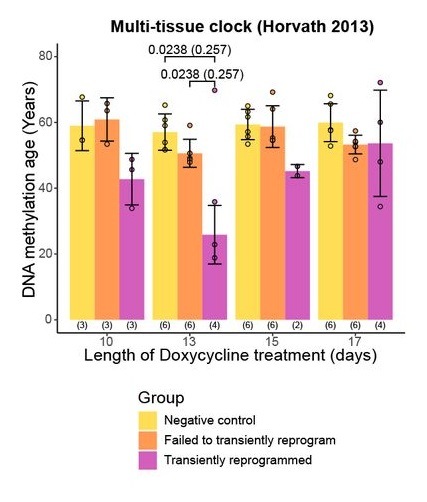

MPTR had substantial positive results. According to Horvath’s 2013 multi-tissue clock, cells that were just under 60 years old became epigenetically equivalent to cells that were approximately 25 years old after 13 days of reprogramming, and the Horvath 2018 skin and blood clock showed that cells that were approximately 40 years old were also epigenetically returned to those of a 25-year-old. The transcriptome, the collection of proteins produced by genes, was also substantially rejuvenated.

There are, of course, quite a few caveats. The most important, of course, is while this experiment was performed on human donor cells, it could not be performed on a human volunteer; therefore, systemic factors that are known to influence the epigenome, such as those found in old blood, did not apply.

Exposing these cells to the OSKM factors was performed with a doxycycline-activated lentiviral package. While this method cannot be safely and effectively used inside a human being, it did allow the time of exposure to be carefully controlled, and such careful control is necessary; 10 days of exposure did not epigenetically rejuvenate cells as well as 13 days of exposure, but the researchers showed that too much exposure (15 and 17 days) led to cellular stresses that aged the epigenome once again. This study had only a few donors, and results after 13 days varied greatly by person.

MPTR did not positively affect the aging hallmark of telomere attrition. When cells were allowed to be fully reprogrammed into stem cells, their telomeres began to extend; however, this partial reprogramming led to moderate telomere shortening even as it rejuvenated the cells’ epigenomes.

Additionally, MPTR did not work on every cell, and these results were obtained after screening procedures that divided cells into failed and successful reprogramming groups. However, even the ‘failed’ group achieved partial successes in many key metrics of cellular aging and health.

Conclusion

While this experiment has shown that it is possible to epigenetically reprogram viable human cells under laboratory conditions, applying such an approach in the clinic would require considerable development of biotechnological fundamentals in order to give each of an individual patient’s cells the exact amount of OSKM it needs to be successfully rejuvenated and no more. This technology is not yet on the horizon.

However, it is feasible that such an approach could be used for the development of cell cultures that can be re-introduced back into an older person. This experiment used fibroblasts, which form collagen, so it is reasonable to imagine a world in which such reprogrammed cells are developed as a therapy against wrinkles and other effects of the aging extracellular matrix. This approach may one day be used to create viable, rejuvenated populations of muscle (incluluding cardiac muscle) and brain cells, and such freshly reprogrammed near-somatic cells may ultimately be the best option in many clinical applications.

Whatever approach proves to be more effective, we look forward to a day in which our own cells can be epigenetically reprogrammed into youthfulness and introduced back into our bodies in order to stave off multiple hallmarks of aging, thus improving our longevity and buying us critical time – time in which further therapies against aging can be developed.

Source: Lifespan.io is a nonprofit advocacy organization and news outlet covering aging and rejuvenation research.

Author: Josh Conway

Source Lifespan.io

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.